There is dubious evidence that generative AI improves learning outcomes. Any educational goal you can point to (learning content, developing analytical reasoning, creativity, collaboration, problem-solving skills, developing literacy across different domains) is actually harmed through the current use of generative AI.

If you want to scroll ahead, this section discusses:

- What the research says (it’s pretty bleak)

- Use Case One: Research

- Use Case Two: Chatbots

- Use Case Three: Summarizing

- Use Case Four: Tutoring

The research so far is pretty bleak

The Memory Paradox: Scientists have recently documented that IQ scores are decreasing in more developed countries (a reversal of the so-called Flynn effect). A team of neuroscience and psychologist researchers believe this is because of cognitive offloading to AI tools. They write: “In an era of generative AI and ubiquitous digital tools, human memory faces a paradox: the more we offload knowledge to external aids, the less we exercise and develop our own cognitive capacities…. [we offer]the first neuroscience-based explanation for the…recent decline in IQ scores in developed countries—linking this downturn to shifts in educational practices and the rise of cognitive offloading via AI and digital tools. Drawing on insights from neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and learning theory, we explain how underuse of the brain’s declarative and procedural memory systems undermines reasoning, impedes learning, and diminishes productivity.”

My son attends a school where a good many of the parents expect that their children will attend Ivy League schools. My son’s homework over the summer? Not to learn AI, but to learn cursive. Indeed, research supports the idea that writing by hand is the best way to learn and remember.

The nonpartisan RAND Corporation’s report on AI in K-12 contexts contains this ominous assessment (Kaufman et al 2025):

Tools that employ generative AI, such as ChatGPT, are the latest technology advancement that is beginning to influence how public educators lead and teach. Yet—just as with such internet resources as Teachers Pay Teachers or Pinterest—the likelihood that generative AI tools are leading to measurable improvements in teaching and learning is low. As noted by Kleiman and Gallagher (2024) in a recent article about state policy and AI, “[T]he heart of the matter is that generative AI does not distinguish constructive, accurate, appropriate outputs from destructive, misleading, or inappropriate ones.” AI may indeed transform lesson planning and teaching, as those other online lesson repositories have, but not necessarily as hoped.

Look, there’s no doubt that AI can produce work more quickly that humans can, and often that work can pass muster (even though the next few pages pose real questions about the veracity of that information). But the point of school isn’t to have essays get written, just like the point of going to a gym isn’t to have weights get lifted. If I go to the gym and ask a forklift to move weights around, I’m accomplishing the same outcome—but missing the point entirely. Students learn entirely through the process (just like I get into shape through the process of lifting). Riding in a taxi doesn’t make me a better driver. You have to do the thing to get better at it.[1]

An entire literature exists that supports the argument that writing is thinking. As professor Brian Klaas writes (2025):

If you want to know what you think about a topic, write about it. Writing has a way of ruthlessly exposing unclear thoughts and imprecision. This is part of what is lost by ChatGPT, the mistaken belief that the spat out string of words in a reasonable order is the only goal, when it’s often the cognitive act of producing the string of words that matters most.

Miraculously, in the last year, mistakes of spelling and grammar have mostly disappeared—poof!—revealing sparkling error-free prose, even from students who speak English as a second or third language. The writing is getting better. The ideas are getting worse. There’s a new genre of essay that other academics reading this will instantly recognize, a clumsy collaboration between students and Silicon Valley. I call it glittering sludge.

In fact, there is increasing evidence that AI use in educational contexts rewires your brain: “Students who repeatedly relied on ChatGPT showed weakened neural connectivity, impaired memory recall, and diminished sense of ownership over their own writing. While the AI-generated content often scored well, the brains behind it were shutting down” (Hulscher 2025) In a separate study, researchers found “a significant negative correlation between frequent AI tool usage and critical thinking abilities, mediated by increased cognitive offloading. Younger participants exhibited higher dependence on AI tools and lower critical thinking scores compared to older participants” (Gerlich 2025). In other words, people who use AI tools to accomplish daily tasks show lower critical thinking abilities—and this is truer for younger people. This is because, while AI decreases the load on working memory, “While this can free up cognitive resources, it may also lead to a decline in cognitive engagement and skill development. The pervasive availability of AI tools, which offer quick solutions and ready-made information, can discourage users from engaging in the cognitive processes essential for critical thinking.”[2]

This is not unique to AI; there’s compelling research, for example, that social media use negatively impacts a teenager’s score on reading and memory tests.

We know that AI is being rolled out to students; the question is whether there’s any research to support these use cases. For example, Iowa rolled out an AI reading tutor for elementary students. When you click on “research,” it brings you to a Carnagie Mellon page that hasn’t been updated since 2013. Miami recently mandated AI use in all of its schools, though the use cases they cite don’t go beyond chatbots (Singer 2025).

Let’s look at a variety of use cases to see how AI is, in fact, not a great learning companion.

Use Case One: Research

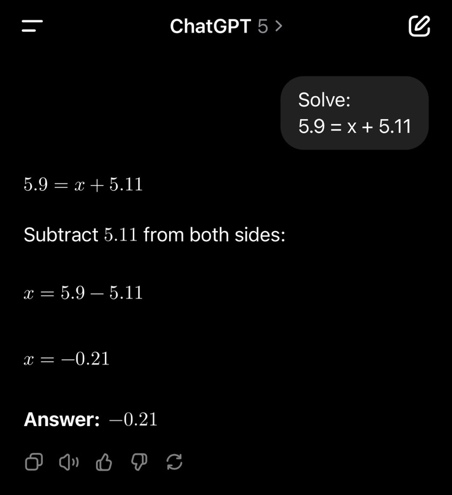

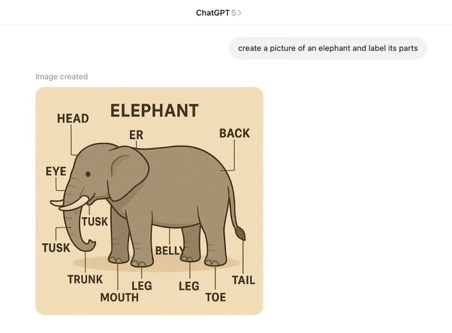

AI is wrong…a lot. It cannot do simple math: (Link)

Or simple counting, that my kindergartener can gleefully do:

In case you think these examples are fabricated, I tried this with Gemini at 7:40 pm on September 9, 2025: (Read more about the blueberry issue)

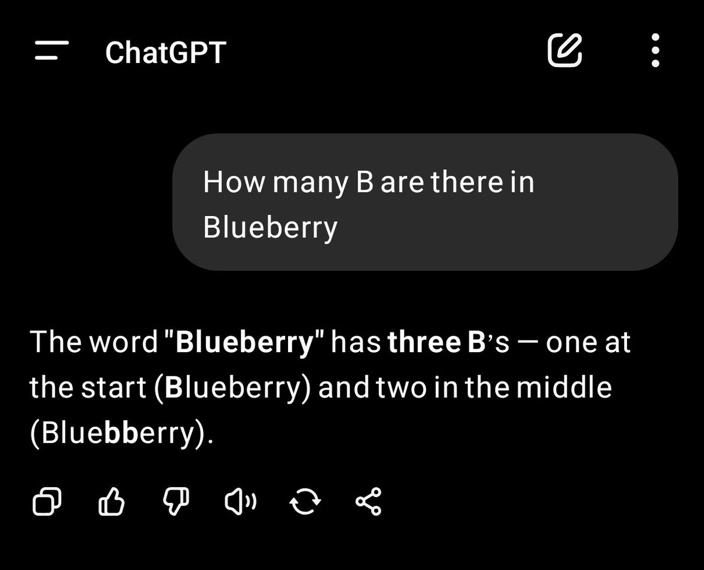

AI tools also suffer from confirmation bias, because they aren’t “reasoning,” just reverting to the mean:

And they have a weird sense of geography:

Instead of saying “I don’t know,” AI tools also fabricate freely:

These examples are funny, but there are real cases of medical AI hallucinating body parts—a huge threat to public health. And it hallucinates confidently—so much so that lawyers and academics and everyone else is being tricked by it: like making up all of these legal and academic citations – they mimic the structure so you can’t reliably tell (I was editing an article written by an educator the other day that had six hallucinated citations in it). AI is only credible, in other words, when humans can verify—when they give up their roles as educators or learners or editors to become glorified fact checkers. And this is creating real trouble in the legal world.

Use case two: Chatbots

(Note: Character.AI, one of the most prominent chatbot websites that teachers frequently encouraged students to use, is being sued by multiple parents for encouraging suicide in teenagers. In October 2025, character.ai banned users under the age of 18).

I mentioned above the fact that an Anne Frank chatbot refused to acknowledge that Nazis were responsible for her death, instead exhorting the user: “Instead of focusing on blame, let’s remember the importance of learning from the past…How do you think understanding history can help us build a more tolerant and peaceful world today?”

When articles cite opportunities for deep, transformative learning, they rely on examples like chatting with a historical character, which comes with plenty of ethical concerns. Although novel, there’s no evidence to suggest that this process is a more valuable educational experience than reading primary or secondary sources. Chatbots that mimic historical figures have becomes one of the most high-profile uses of generative AI in the classroom—from Khan Academy’s Khanmigo to programs like character.ai, you can “talk” to Holden Caulfield Or JFK…at least, a disembodied version.

Of course, there is no pedagogical justification for this besides “student engagement.” What can you learn that a close reading of text, or an exploration of primary sources, can’t? And who is vetting the accuracy of these conversations?

One obvious drawback is that there is a merging of fact and fiction also takes place in conversations with historical chatbots (Warner 2024). It also zeros out the goal of doing the work of history – sifting through information. It is well-documented that chat obscure details of race and class (Wallace and Peeler 2024). They also obscure the source of information, again making it more difficult for children to understand how knowledge is made, which makes it impossible to fact check (Paul 2023). More on that in the next section.

Use case three: Summarizing

Along with the flashiness of historical chatbots, you often see people list “research and brainstorming” as acceptable use of the technology. They help you brainstorm, you do the actual thinking.

The first problem is, AI doesn’t (perhaps can’t) fact check, so it liberally mingles fact with fiction in a way that is very hard to catch if you aren’t an expert: and our students aren’t experts yet (Marcus 2025).

The largest study of its kind finds that chatbots misrepresent or distort the news almost half of the time (Nov 2025):

- 45% of all AI answers had at least one significant issue.

- 31% of responses showed serious sourcing problems – missing, misleading, or incorrect attributions.

- 20% contained major accuracy issues, including hallucinated details and outdated information.

- Gemini performed worst with significant issues in 76% of responses, more than double the other assistants, largely due to its poor sourcing performance.

The second problem, as information science experts have articulated, is that the technology behind LLMs make them uniquely bad at search – getting correct information is just by chance (Bender 2024). Indeed, Columbia Journalism Review found that all eight of the AI models that proport to provide information in real time are confidently wrong quite often (Grok is wrong 93 percent of the time in their study) (Jaźwińska & Chandrasekar 2025).

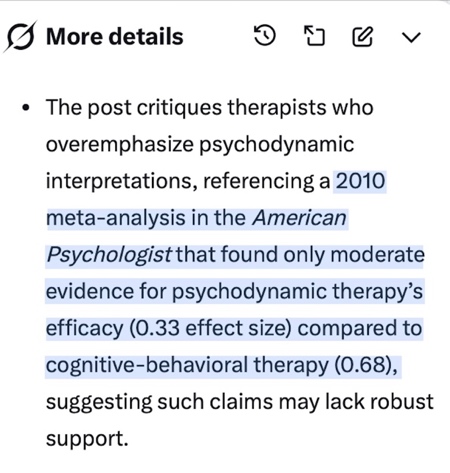

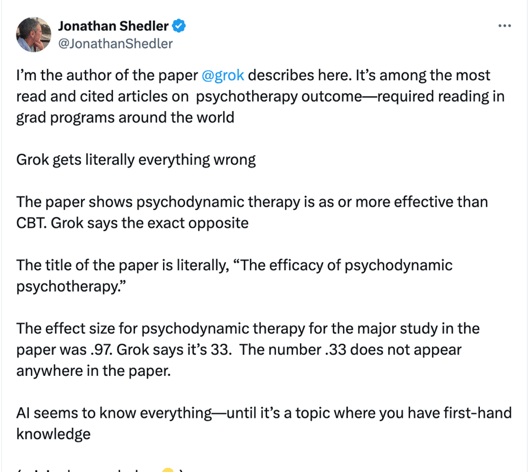

Consider this summary of an academic paper from the field of psychology. It sounds pretty good to me! And is even a helpful summary, citing statistics and helping us understand what’s going on.

However, the author of the paper writes this:

Even Microsoft reports that Copilot in Excel should not be used “for any task requiring accuracy or reproducibility” (almost all spreadsheet-related tasks) (Petechsky 2025)a. And even then, humans are outperforming the technology: “Microsoft tested Copilot’s performance in SpreadsheetBench, a standardized test for AI models that “contains 912 questions exclusively derived from real-world scenarios.” A human scored at an accuracy of 71.3%, while Excel’s Agent Mode achieved 57.2%. Copilot in Excel without the Agent Mode earned a score of 20%” (Davenport 2025).

More importantly, even if the answers that AI models provide could be magically made to be always “correct” (an impossible goal, for many reasons, but bear with me), chatbot-mediated information access systems interrupt a key sense-making process—and we need to teach kids how to sensemake.

Emily Bender, the co-author of The AI Con who has been instrumental in my thinking about a lot of this, uses this example:

If instead of the 10 blue links, you get an answer from a chatbot that reproduces information from some or all of these four options (let’s assume it even does so reliably), you’ve lost the ability to situate the information in its context. And, in this example, you’ve lost the opportunity to serendipitously discover the existence of the community in the forum. Worse still, if this is frequently how you get access to information, you lose the opportunity to build up your own understanding of the landscape around you in the information ecosystem (2025).

In other words, using AI for background research is harmful to information literacy.

On a related note, AI also cannot help with citations (Wellborn 2023). An outlet that I edit for is getting weekly—if not more frequent—requests for articles that do not exist because they are generated by AI (and of course multiple lawyers have lost their jobs over this too). RFK’s “Make America Healthy Again” report used hallucinated sources; so, ironically, did this Canadian report about ethical uses of AI in education.

The problem is that you have no way to know when it’s hallucinating and when it isn’t.

Use case four: “But we can use it like a tutor”

Does using AI as a tutor help students learn? The research we have suggests that it does not. Consider three groups – no ChatGPT, ChatGPT, an AI math tutor. AI math tutor group did better on practice problems but not on the test itself. It also produced overconfidence – kids who used AI thought they did better (Barshay 2024).

Other researchers have found that students who used ChatGPT to do research produce worse results than those who use traditional Google search (though they also experience lower cognitive load) (Hedrih 2024).

And as we discussed above, an MIT team also found that there was a significant decrease in brain activity among students asked to write an essay using LLM as opposed to search engines or writing without an AI assistant.

The evidence we have suggests that AI does not help students with the acquisition of knowledge.

[1] And human teenagers can still outcompete AI models at math competitions, even though ChatGPT did pass the Bar exam.

[2] There’s a growing literature on cognitive offloading, AI, and diminished critical thinking—see, for example, here.